How S3 API compatibility lets you use any cloud

If you've been around distributed systems long enough, you learn to separate interfaces from implementations.

Interfaces are what let systems evolve. Implementations get rewritten every three years.

The S3 API won because it was an interface that stayed boring. Once something is predictable enough, engineers start building assumptions on top of it.

Standards enable choice

AWS S3 is an implementation of the S3 API: the implementation gave rise to the interface. Now many storage providers, including Tigris, implement the S3 API interface for interoperability and portability across clouds. Don't take for granted how amazing this is— not only for the choice it creates, but for the fact that it runs counter to xkcd's famous comic on the proliferation of standards: https://xkcd.com/927/. xkcd is almost never wrong.

If compute, network, and storage expose stable, well-understood interfaces, then the workloads you build on top of them become portable, almost by accident.

Today, those interfaces are fairly clear:

- Compute: Kubernetes and OCI

- Network: Protocols like TCP/IP, DNS and TLS

- Storage: POSIX for files and the S3 API for object storage

Each of these standards does the same thing at a different layer: they define what the system expects, not how it's implemented. This distinction is what lets clouds become interchangeable.

Database portability is harder than storage portability— strong semantics are difficult to standardize. This is probably a factor in why "just use Postgres" has become a popular coping mechanism. But even databases increasingly rely on portable storage underneath, and we'll come back to that briefly.

Why is S3 compatible storage so portable?

We've talked about S3 compatibility before, but in short: it's weak semantics. There are no schemas, no transactions, no coordination primitives. S3 doesn't try to be a database. Databases exist to provide these things.

S3 API provides durable objects, addressable by key and retrievable over HTTP with eventual consistency. Those minimal guarantees are easy to implement across wildly different architectures.

The adaptability of the interface also explains a subtle shift in cloud native system design: durability and recovery live in object storage, not inside engines.

Databases like YugabyteDB and CockroachDB use S3-compatible storage for backups and recovery, with YugabyteDB also writing their WAL to object storage. Newer systems like TiDB's serverless offering and SlateDB go further, treating object storage as the backbone of their architecture. The engine stays opinionated; the state becomes portable.

But that's enough about databases.

What "Use Any Cloud" actually looks like in practice

Using any cloud doesn't mean you wake up every morning and roll a die to pick a provider. In real systems, portability shows up in how you design defaults, not in how often you migrate.

Business as usual might look like a single cloud deployment, but you don't panic when costs spike, compute isn't available, a contract changes, or a region goes down— you redeploy your workload somewhere else.

Most teams don't ever actually "go multi-cloud" in the corporatist definition of the word. They're just more flexible in using the right cloud for the job.

We've written before about Nomadic Compute, a workload design where you define a workload outside any particular cloud and deploy it to the "best" compute available at the time. Chase the cheapest GPUs if you like, but even teams who are relatively price insensitive benefit from the flexibility. This is where BYOC (Bring Your Own Cloud) platforms enter the picture.

BYOC platforms make portability the baseline

A new class of platforms assumes portability as a baseline. They deliberately restrict themselves to standard interfaces so workloads remain movable.

They don't replace cloud providers. They sit above them.

All of their state is external to the particular cloud, and you can guess where that state is stored: S3 compatible object storage.

Nuon: shipping software into customer clouds

Nuon ships software into customer clouds without rewriting it for every environment. Aggressive standardization assumes:

- Kubernetes for compute

- OCI images as the deployment artifact

- object storage for durable state

Object storage is what lets the state outlive clusters, upgrades, and redeployments without becoming entangled in each customer's cloud configuration.

Northflank: a many clouds control plane

Northflank behaves like a portable control plane. From the developer's perspective: service definitions, build pipelines, and runtime expectations don't change. Only the placement does.

Similarly, Northflank uses Kubernetes, OCI, standard networking, and S3-compatible object storage for artifacts and state. Northflank Stacks are like a multi-cloud by default version of Terraform Stacks (prev. Terraform Modules) where the state is external to the given cloud.

This is the principle in action: clouds are execution environments, not platforms.

SkyPilot: moving compute where it makes sense

SkyPilot approaches portability from a compute economics perspective: data is traditionally expensive to move, and compute pricing varies widely. Given a workload definition and a list of all the clouds you use (a "Sky"), their optimizer finds the cheapest and most available compute. Data is stored in S3 compatible object storage that interops with any provider.

You get GPU training where GPUs are available, batch jobs where spot capacity is cheapest, and experiments wherever startup latency is lowest. S3 compatible storage is the durable layer that prevents bespoke data migrations for each cloud hop.

What these platforms have in common

These platforms converge on the same constraints:

- Kubernetes for compute

- Standard protocols for networking

- S3 compatible object storage for state

None of these platforms assume you'll constantly move workloads across clouds. They promise that you don't have to redesign your system if you ever need to.

Portability is for operational consistency, not migration theater.

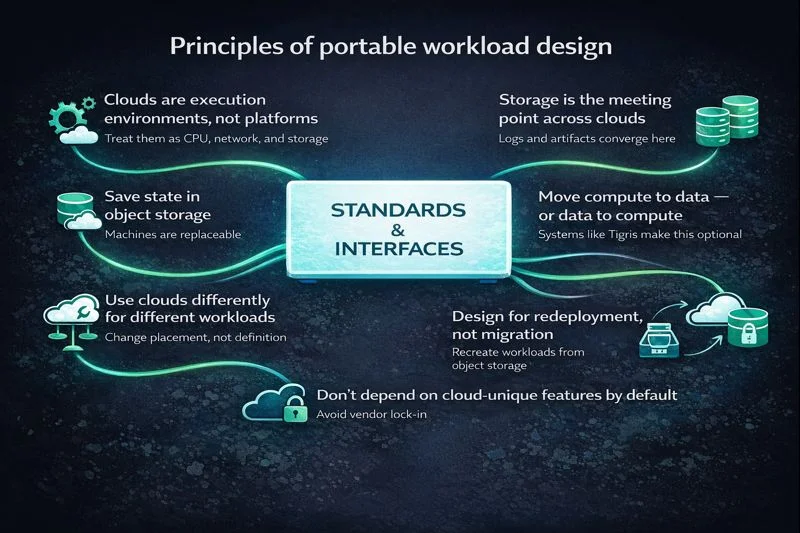

Principles of portable workload design

BYOC platforms are designed with a set of principles that are useful, even if you never adopt one directly.

Clouds are execution environments, not platforms

Your workload should assume CPU, memory, network, and storage, not provider-specific services.

Save State in Object Storage, Not Machines

Machines are replaceable. State is not.

Storage is the meeting point across clouds

Artifacts, logs, checkpoints, and outputs converge here.

Move compute to data — or data to compute

Traditionally, data was the anchor. Systems like Tigris make that assumption optional.

Use clouds differently for different workloads

With standard interfaces, your workload definition doesn't change. Only placement does.

- Latency-sensitive APIs in one cloud

- GPU-heavy training jobs in another

- Batch analytics where spot capacity is cheapest

- DR or compliance workloads isolated in a specific provider

Design for redeployment, not migration

You don't move workloads. You recreate them based off state saved in object storage:

- redeploy compute

- reattach storage

- replay logs

- warm caches

If the only thing you must preserve is data behind a standard API, everything else becomes cattle.

Don't depend on cloud-unique features by default

This doesn't mean "don't use managed services." It means know which commitments you're making. And S3-compatible storage is not a commitment you need to manage. It's a standard.

Conclusion: S3 compatible storage is the backbone of portable workloads

Kubernetes made compute portable. Protocols made networking portable. S3 compatibility did the same for storage. Together with BYOC platforms and portable workload design, these pieces finally come together into something practical: workloads that aren't tied to a single cloud's implementation details.

The primary goal isn't cloud-hopping for its own sake. It's operational consistency. Your systems fit cleanly into whatever compute, network, and storage you choose, without special cases or rewrites.

There are, of course, meaningful secondary benefits:

- Performance: workloads are co-located

- Compliance: workloads are easily deployed to isolated environments

- Cost: avoid markup on the underlying compute and storage

- Vendor lock-in: you choose the cloud

But those are outcomes, not the motivation.

What really matters is that the system behaves the same everywhere. That reliability is what makes portability usable instead of theoretical.

And this is where Tigris pushes portability further. By moving data closer to compute by default, Tigris removes one of the last sources of friction—so both your data and your workloads can run where it makes the most sense.

Ready to build portable workloads? Get started with Tigris and see how S3-compatible storage enables true cloud portability.