Global Replication Made Easy

This is a transcript of my talk Global replication made easy at Devops Days Halifax 2025. This transcript was prepared based on my speaking notes and the end talk may differ from this transcript. As this is a talk, the writing style of this post is much more causal. A video of this talk will be embedded on this page as soon as it is available.

Hi, I’m Xe. I work at Tigris Data as the Senior Cloud Whisperer. Today I’m going to talk about the hard problems with global replication. I hope that by showing you how Tigris works you can be inspired to create your own globally replicated systems.

Today I’m going to talk about the problems involved with making data global, the different approaches you can try, how Tigris solves the problem, and then I’m going to end with ideas on how you can make your systems global without making things too complicated.

Before we get this started, let me introduce myself. I’m Xe Iaso with a capital i. I’m an avid blogger with about 550 articles and counting. I stream programming on Fridays, I’m a bit of a gamer, I live over in Ottawa, and I fight the menace of AI companies destroying the internet in my spare time. The little goofball with brown hair is Anubis, the mascot for Anubis, the bot filter I make. Ask me more after class.

About Tigris

Just in case you haven’t heard about it yet, Tigris is a globally distributed S3-compatible object storage. It’s a drop-in replacement for your existing object storage provider, even as far as letting you drop-in your data. If you want to know more about that, again, see me after class. Either way: here’s the big problem that Tigris has to solve:

Tigris makes your data available in 13 regions. Each of these regions can potentially be authoritative for any object in any bucket. There is no “leader” that dictates who owns what. Every region has its own root copy of the database and has to keep itself in sync with every other region.

Let’s add this to our list of hard problems that need to be solved:

- Your data is stored globally with any region potentially being in charge of it.

To make things extra fun, nothing is immune to entropy. If you don’t take active care to make sure that data stays usable, it will be lost and it is only a matter of time until it happens.

Data is very high inertia. Once you put it somewhere, it takes a lot of effort to move it. Once you put it somewhere, there’s a near implicit expectation that the data will stay there. This combined with the fact that storage devices, batteries, RAM, and CPUs are constantly decaying with every time they’re used means that we have another thing to add to the hard problems list:

- Your data is stored globally with any region potentially being in charge of it.

- You expect your data to always be available no matter what.

Come hell, high water, or fibre-seeking backhoes, you want your data to load when you need it.

You don’t just expect your data to be available globally, you want it to be fast. Ideally, you want it to be so fast that you forget that Tigris is even there. Tigris wants to make your data globally available, durable, and low latency so that you can let the details slip into the background.

This is the total list of hard problems:

- Your data is stored globally with any region potentially being in charge of it.

- You expect your data to always be available no matter what.

- Your data is available with the lowest possible latency.

Tigris wants to make sure that your data is stored globally, durable enough to be always available, and additionally available with the lowest possible latency. Any one of these problems alone is hard to solve. Two of them combined are even harder. But Tigris solves all three. How does it do that?

An illustrated primer about Object Storage

At its core, object storage is about the most unopinionated database you can imagine. When you put data into object storage, you give it the data, the metadata for that data, and a key name. Then it stores it. When you want that data or metadata back, you give it the key and it gives you what you want. That’s it, that’s the entire thing in a single paragraph. The devil as always is in the details.

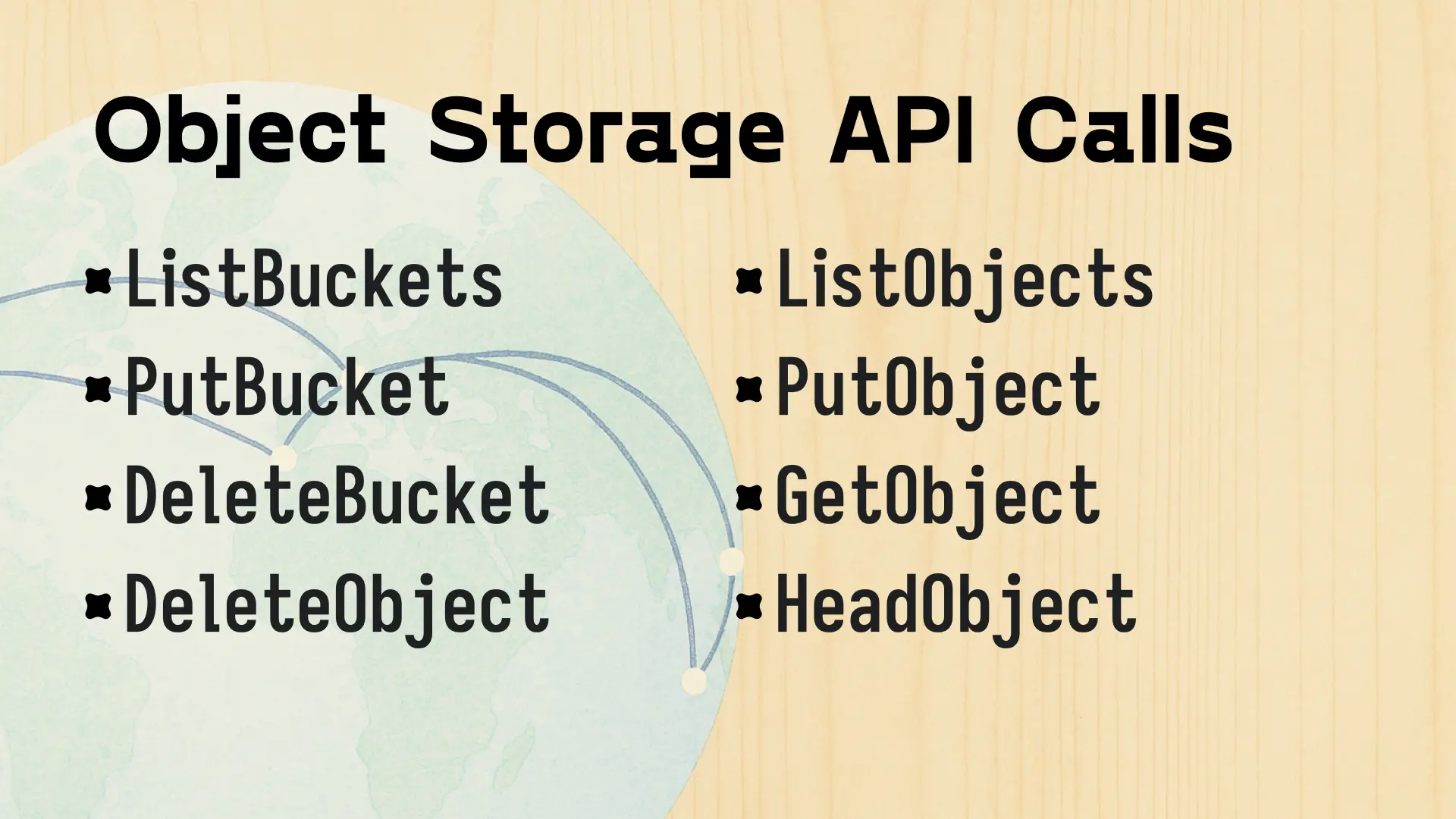

You can summarize every use of object storage down to these API calls in no particular order: ListBuckets to list buckets, PutBucket to create a new bucket, DeleteBucket and DeleteObject to hide all evidence of your sins, ListObjects to...list objects, PutObject to add new data to the cloud, GetObject for grabbing that data from the cloud, and HeadObject to get that sweet juicy metadata. All the calls are basically self-describing.

Well, except for PutBucket, that made sense before The War.

In order to help get the point across with how data gets global, let’s consider an example bit of data, such as this pic o Rick:

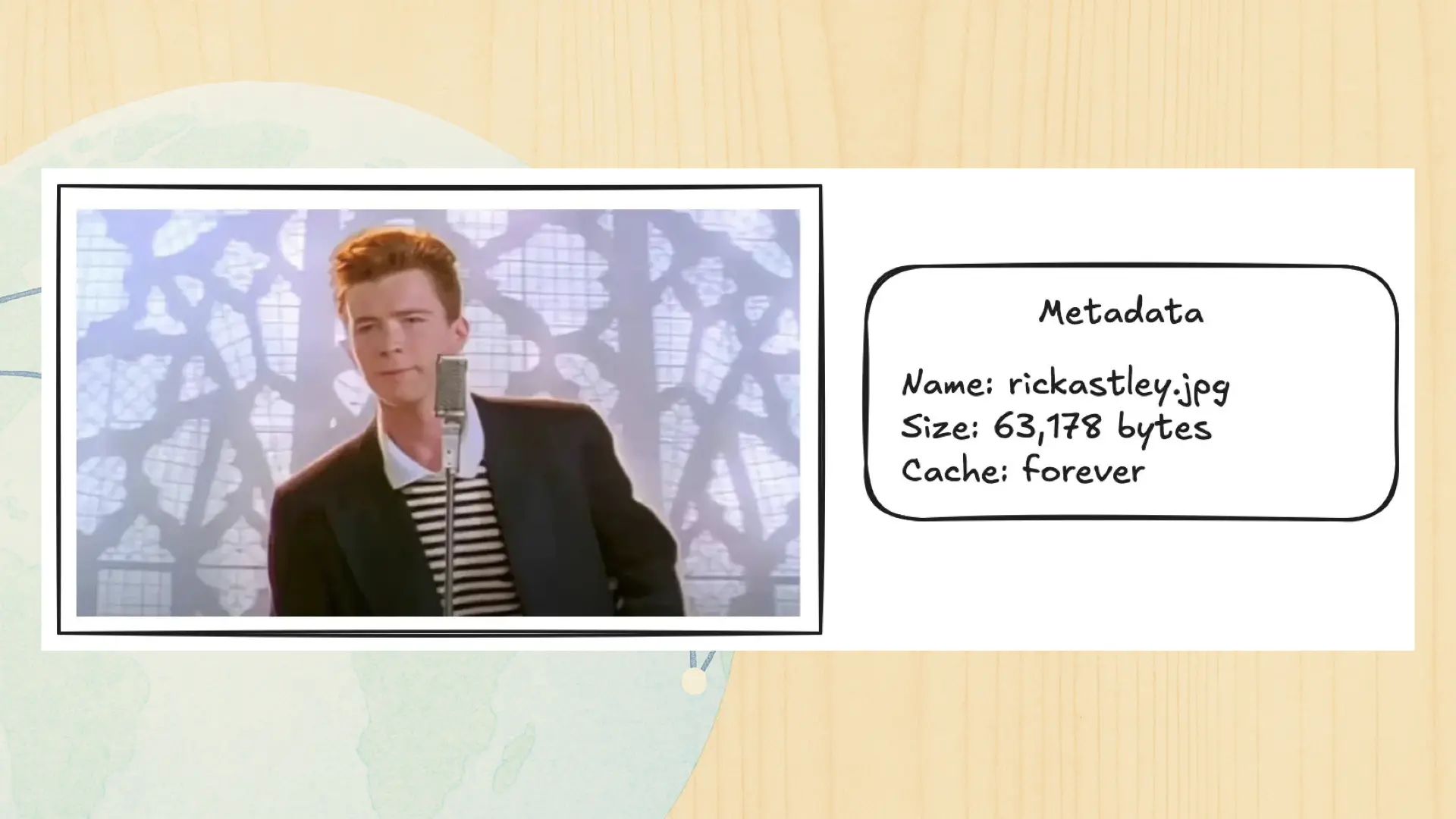

Raise your hand if this is the funniest thing you’ve ever seen. Either way, when you put this picture into an object storage bucket, you also attach some metadata to the file:

In order to make things clear, I’m putting data in square boxes, and the metadata goes into those rounded squircles. Just keep that in mind for the diagrams you see in this talk.

Methods of replication

So let’s cover some of the ways that you can go about doing this kind of globally distributed replication. To keep things simple, I’m going to talk about the two basic flavours of it: pull-oriented replication and push-oriented replication. As always with distributed systems, both of these models have their upsides and downsides and the ideal model incorporates the best aspects of both of them.

Pull-oriented replication

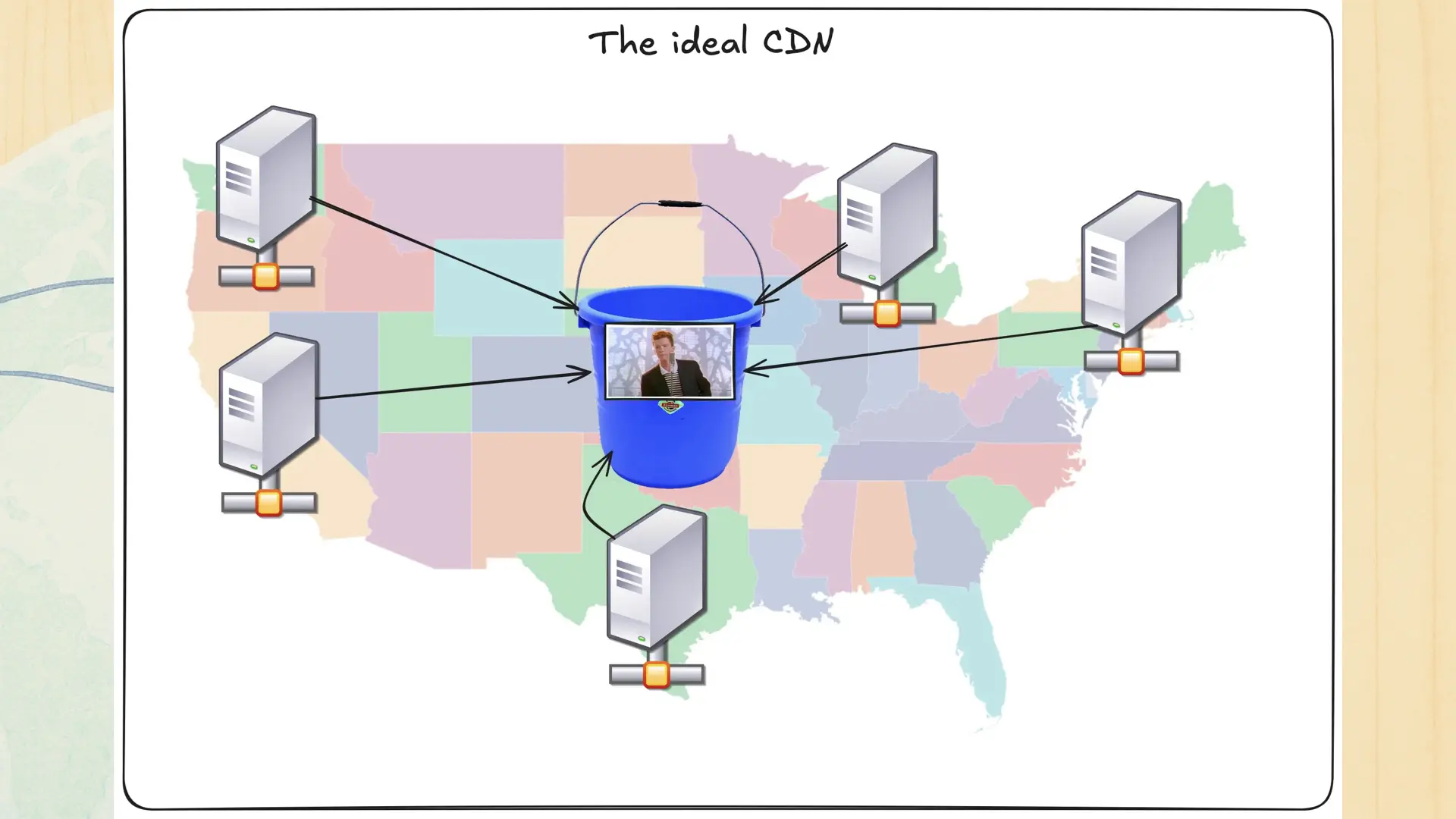

The best example for a pull-oriented replication model is a content distribution network or CDN.

With a CDN you have a source of truth such as an object storage bucket and a bunch of edge nodes all over the world that make local copies of the data in that source of truth. When users load images, music, or video, they hit those edge servers instead of that source of truth. This means that you gain an edge over the speed of light so that users load things fast. This works well enough for most websites across the world. The basic design is well-understood and you probably encounter them constantly without knowing it.

However there’s a hidden cost that can be a problem at scale. The edge nodes query objects in the source of truth on demand. This means that the first time that someone in Chicago requests that picture of Rick Astley, it can take a few milliseconds longer for it to load. During that load, the browser shows an empty box. Sure, there’s ways to work around this with clever placeholder logic, but at some level, you’re limited by the slowest part of the process.

Push-oriented replication

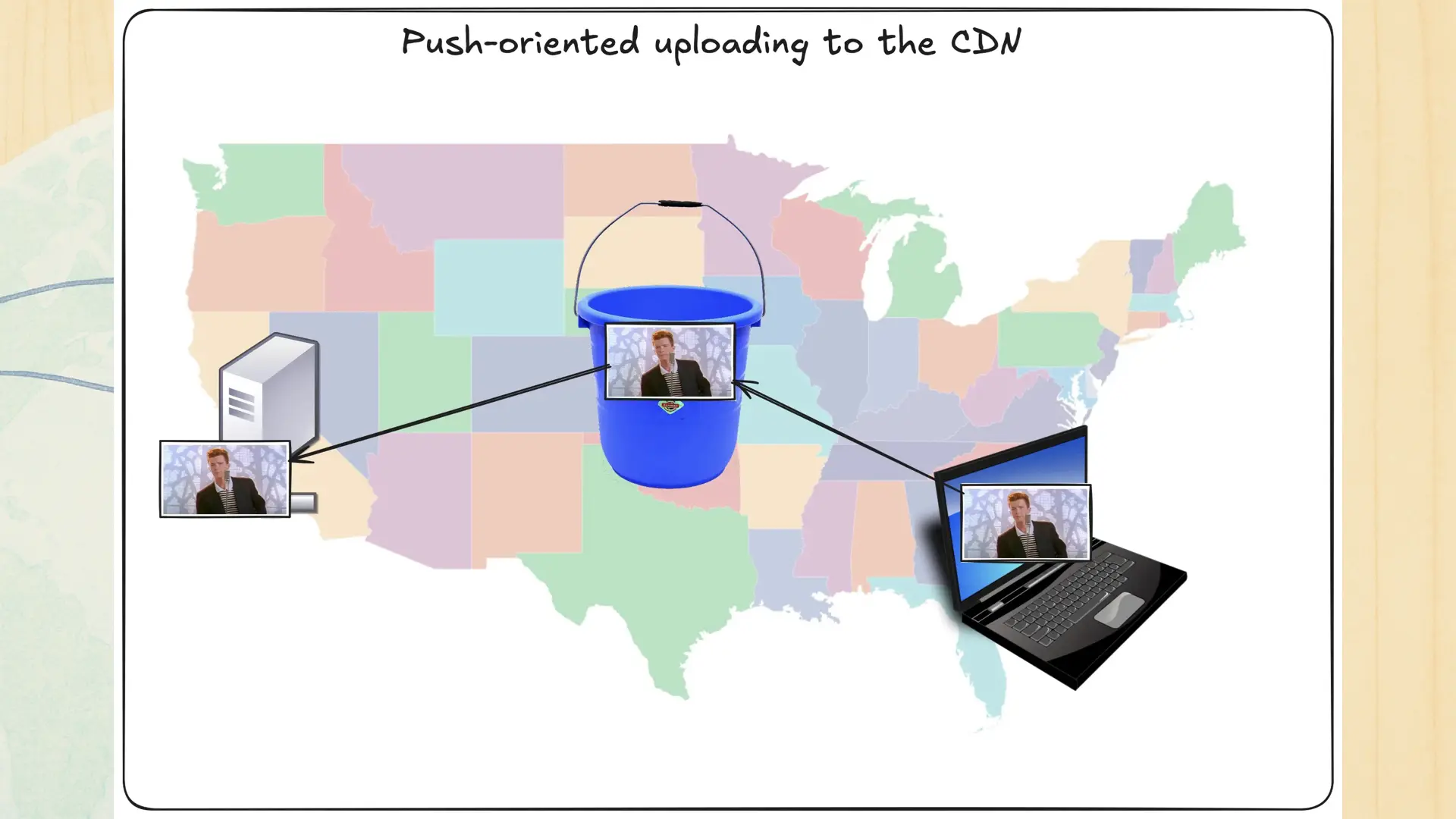

What if there was a different way? Let’s imagine an architecture where the data is pushed whenever anything changes.

This is basically what push-oriented replication does. You push to the bucket, it pushes to the edge servers, users hit the edge servers, something happens, and then you make enough that you can retire. The main innovation is that publication creates wide distribution automatically. This means that everything loads fast, at the cost that your bucket is usually append only.

But what about incredibly local news? This wouldn’t work as well if you’re making a CDN for a global news agency and someone on staff posts a story about how the Senators got ripped off again because the Canadiens won again. That news probably only is relevant to a small group of people in Ottawa and Montreal, there’s no reason you need to cache the photos from that game all over the world. Who in Singapore, Taiwan, or Johannesburg is going to care about hockey?

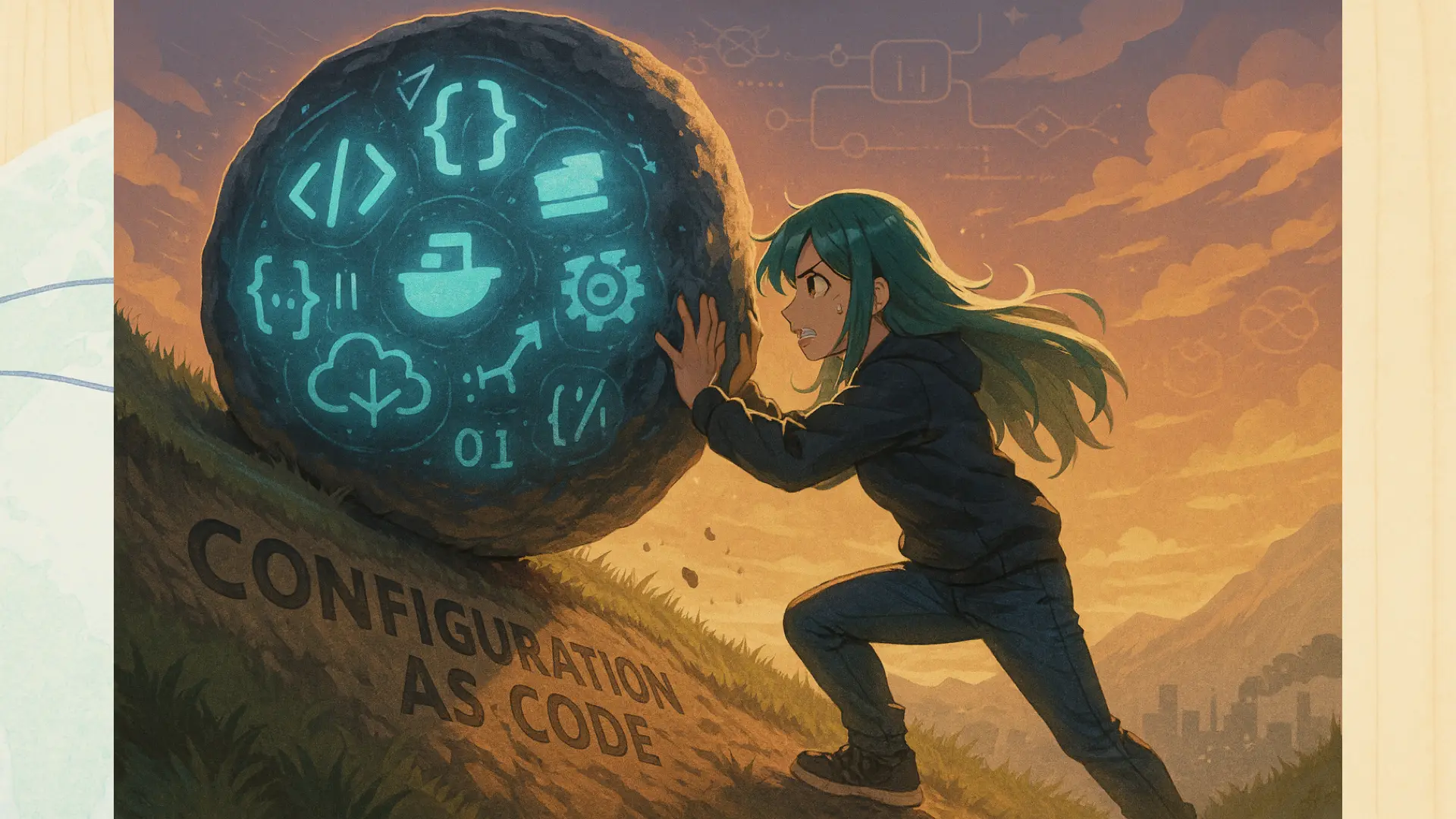

This is how the CDN configuration becomes more than “push button, receive bacon”. All of the rules for eager pushing, high grade customizability, virtual presence, single instruction multiple dispatch, button bloat, and more just add up into this massive boulder that you just keep pushing up that hill. It’s like that one greek guy, syes-ih-fee-us? It’s a chore.

I can't capture this very well in the text version of this talk, but the joke is that I am intentionally mispronouncing Sisyphus as a reference to Bill and Ted mispronouncing Socrates.

So what if you could just kick that boulder away forever? Let’s imagine a world where your objects are global by default so you can fetch them from anywhere quickly, but also at the same time not having to eagerly cache them everywhere.

Okay, there is an asterisk here. It’s anywhere on the planet Earth. If you have a big Martian customer base, this talk can’t help you...yet.

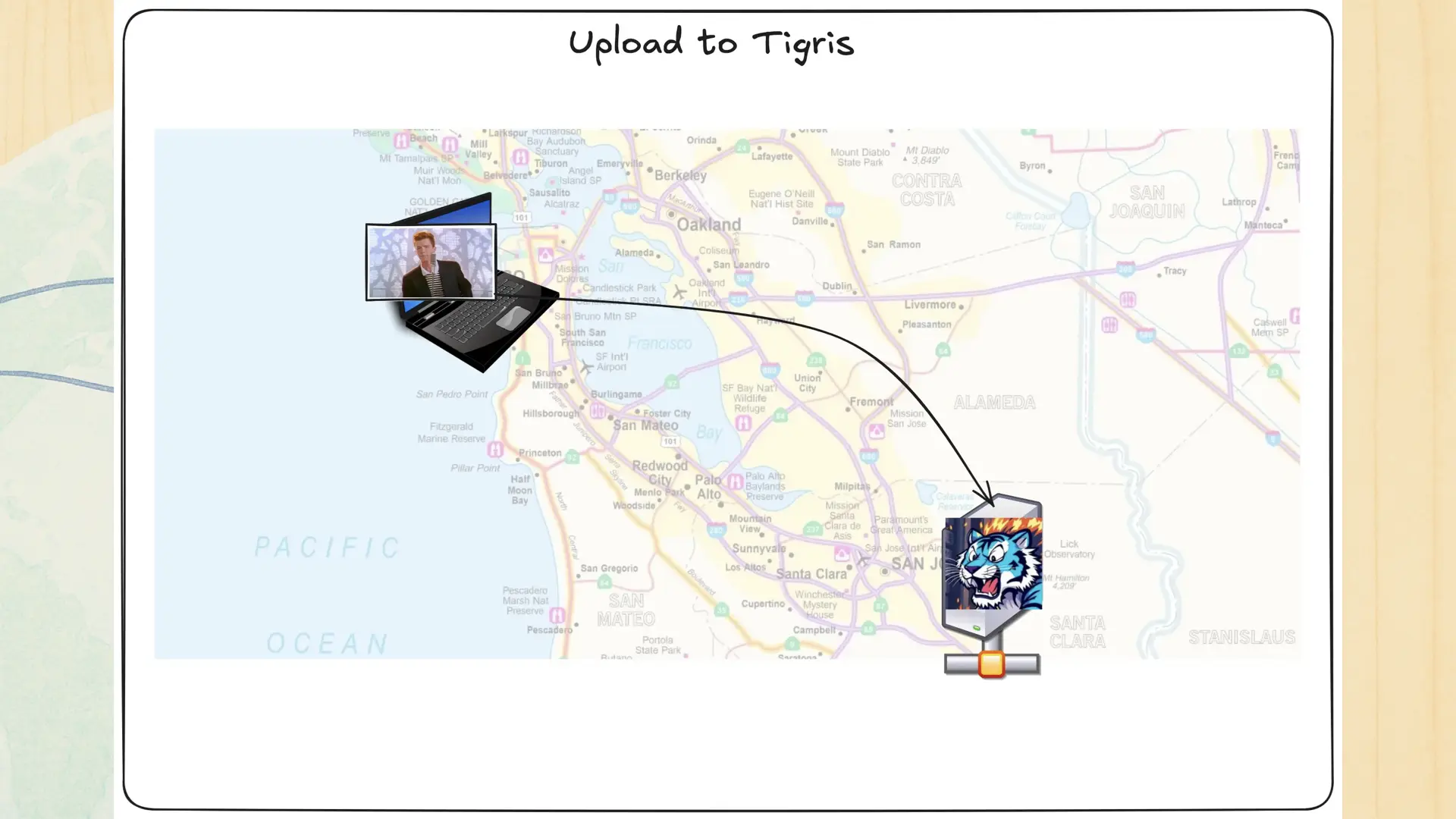

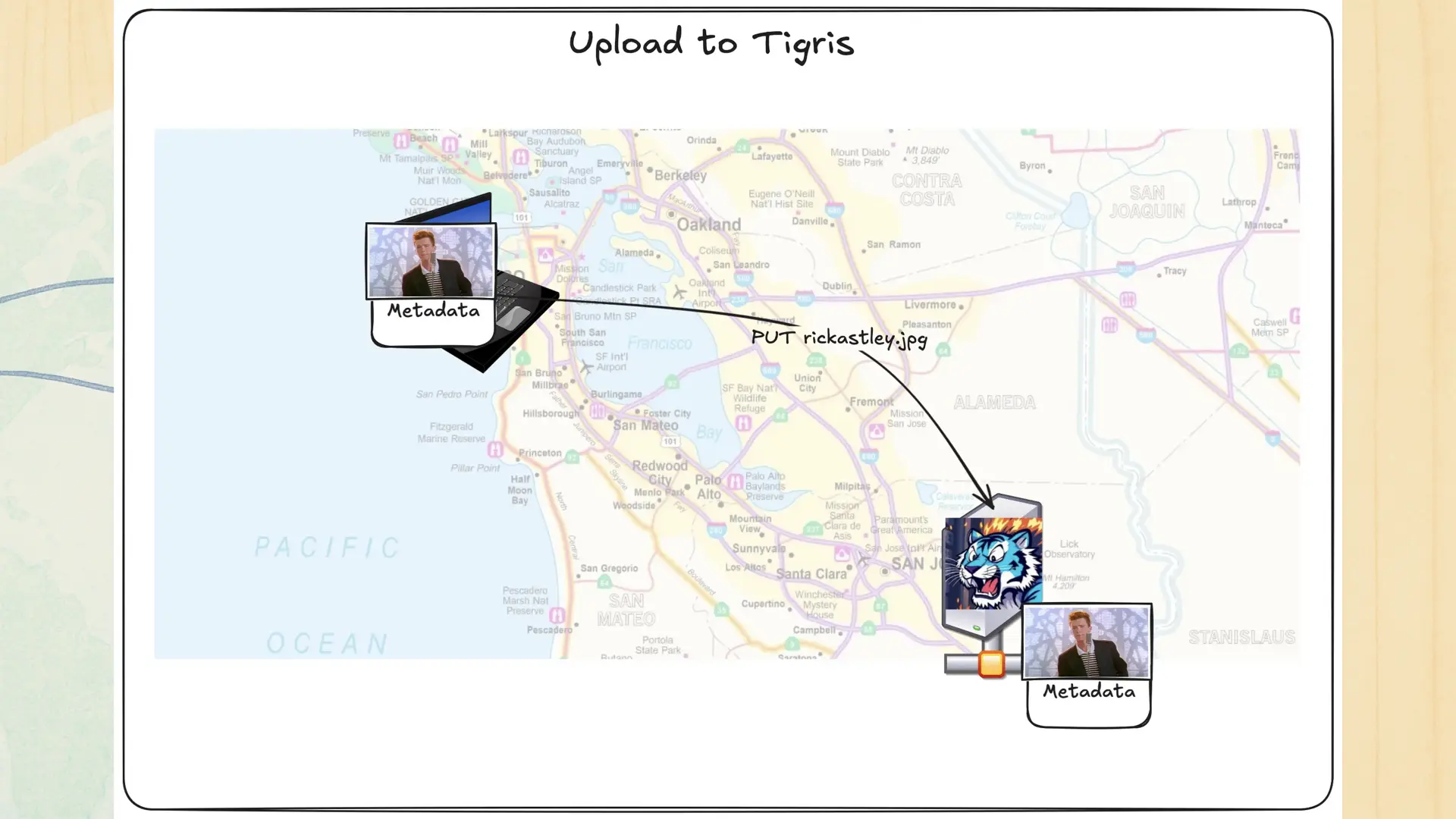

Let’s say you have that good old pic o rick (pronounce like pickle rick) and you upload it to Tigris in San Jose from your laptop in San Francisco. What happens next? How do the other Tigris regions know about the file? If they’re not told they’ll just serve a 404.

That would be, uhhh what’s the scientific term? Bad? Yeah, let’s go with bad.

There’s several ways to do this, let’s think it out a bit:

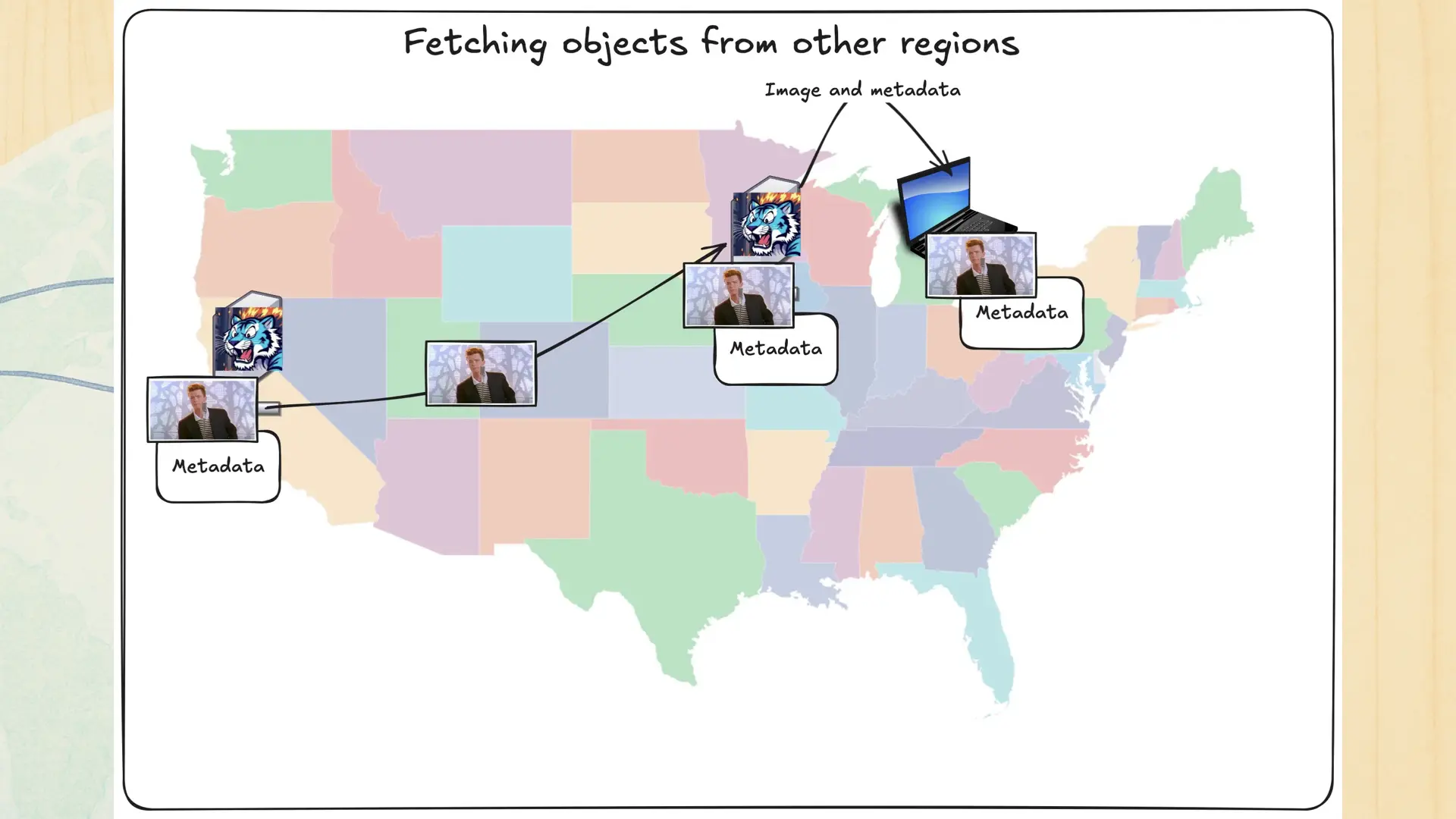

One way you could do it is you could ask every other region if an object exists, then just pull over the data when you need to. This would make the full return flow look like this:

Your user makes a request for the pic o rick to Chicago, the Chicago region asks san jose for the data, it gives that data, and now Chicago can serve that data too. In theory, this could work, but there’s one big problem with this:

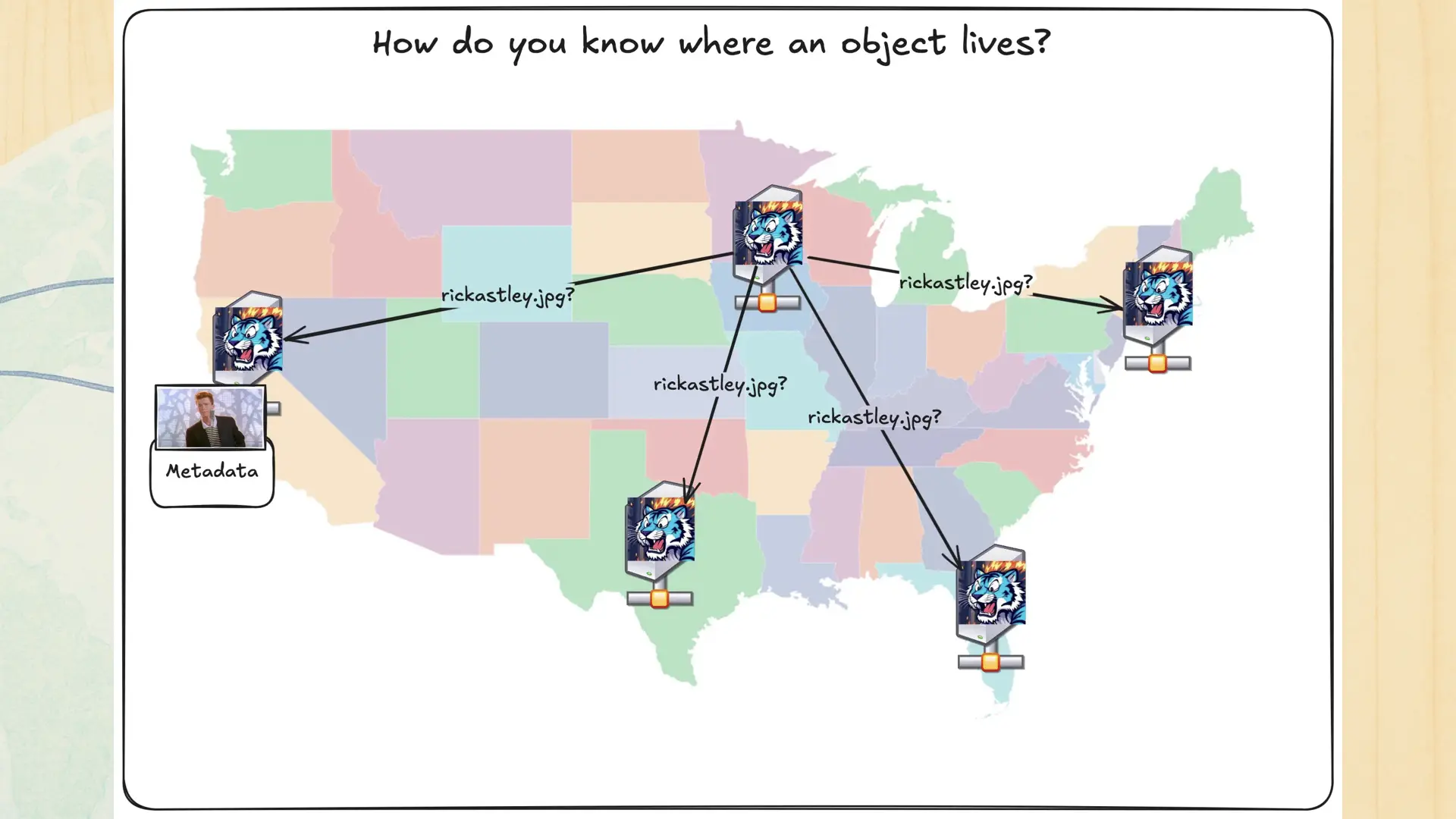

Any region can be in charge of any object. In the worst case this would mean that requesting any object would mean asking all of the Tigris regions for that data. Just imagine this:

Your architecture would just ask everywhere about everything, all at once. Not only would you not get a bagel with this, it’d just be so slow that nothing would work reliably. You’d be constantly fighting the speed of light instead of using it to your advantage. This scales across continents poorly. Worse, this would be vulnerable to one of the greatest sins of distributed systems:

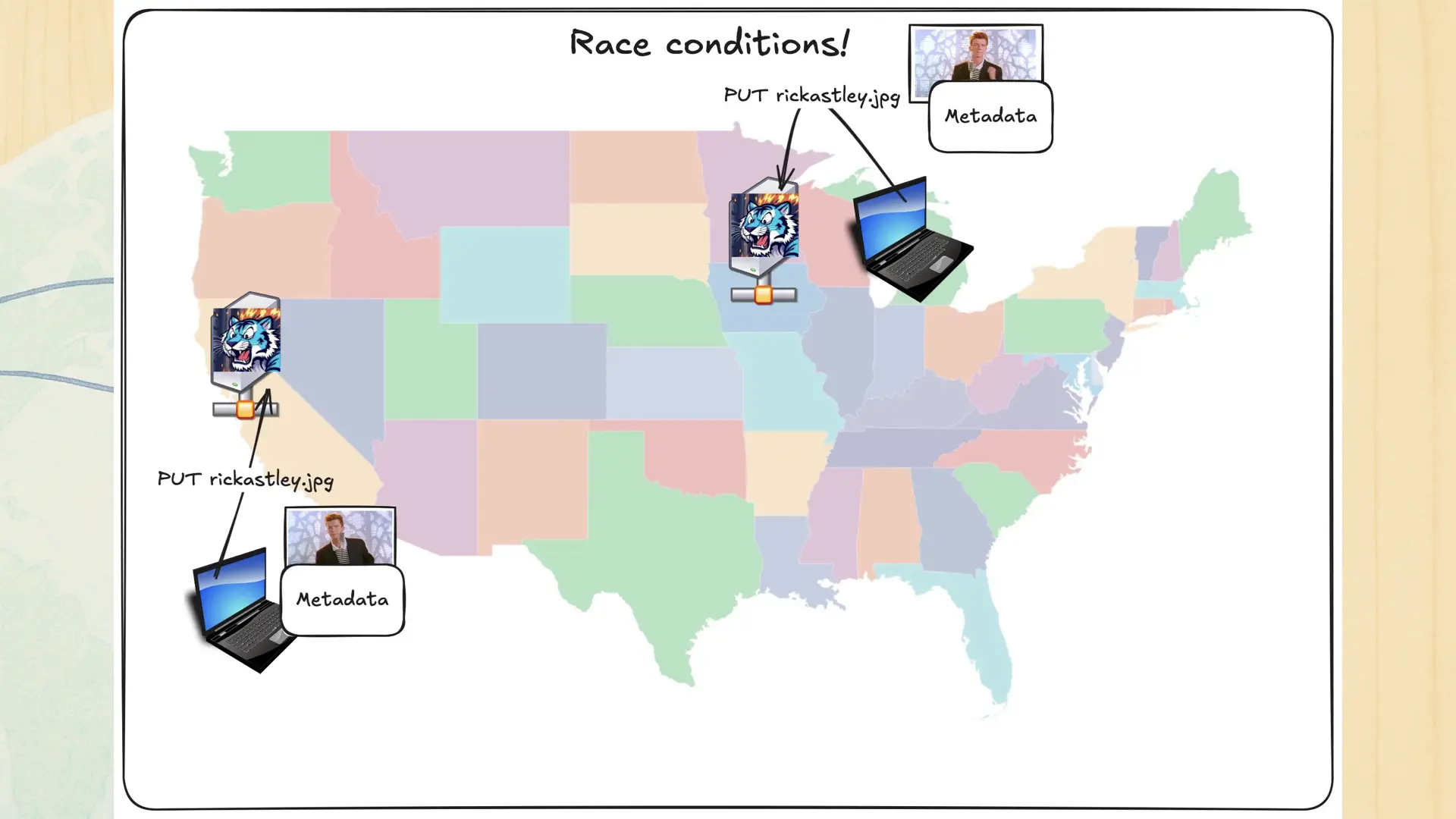

Race conditions. If fear is the mind killer, race conditions are the prod killer. What happens if two users upload different files with the same name at different times in different regions?

You get something like this. How do you know which object is the right one? Time? Region weight? The phase of the moon? Speed of light replication latency? Tarot cards? It’s not viable in production.

How Tigris does replication

So, with all that out of the way, let’s get into the fun stuff: how Tigris does replication. There’s an old saying in SRE: all models are wrong, some are useful. Tigris uses a hybrid of push-oriented and pull-oriented replication. It eagerly pushes out the metadata, but only pulls the data when it needs to.

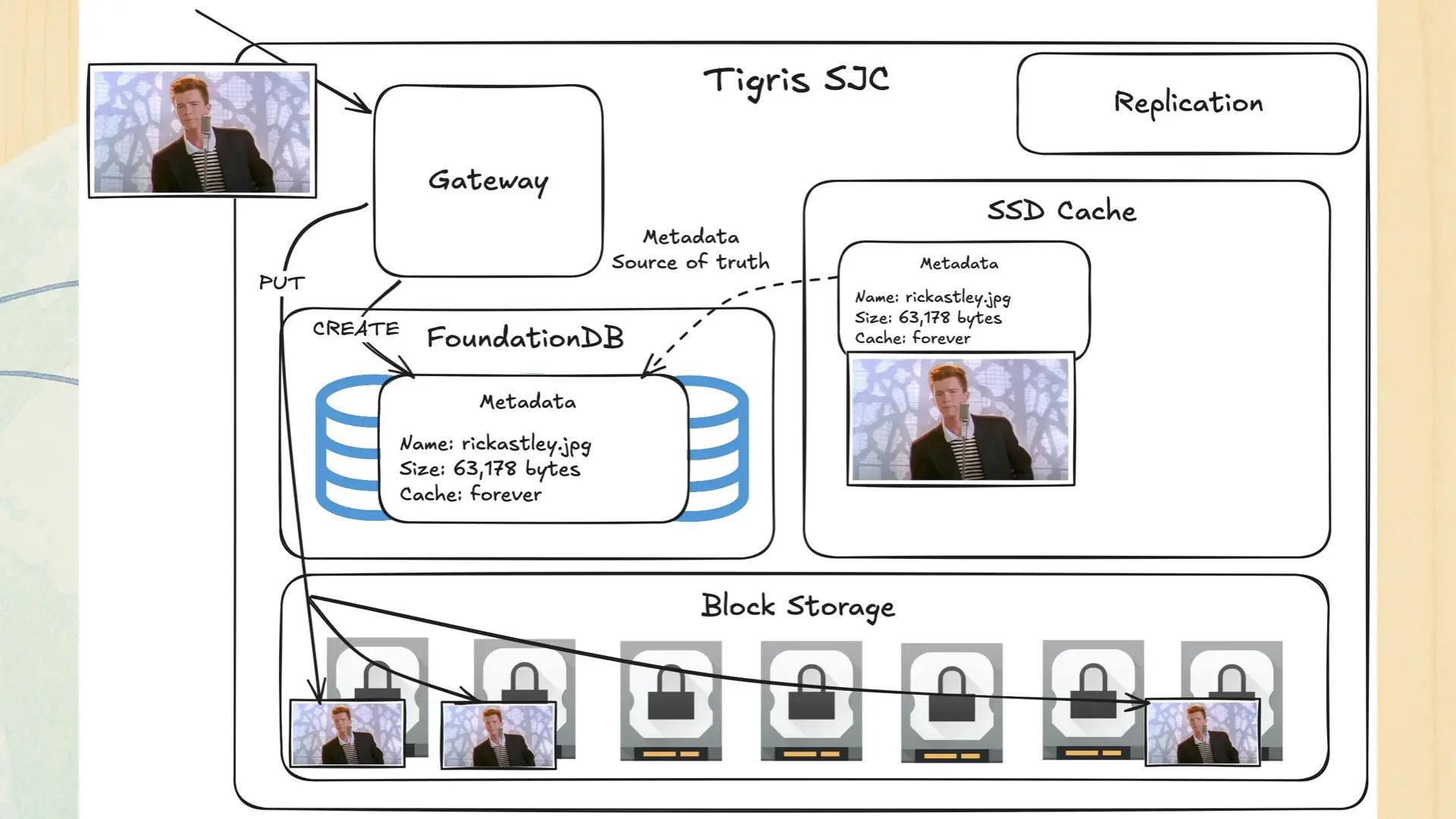

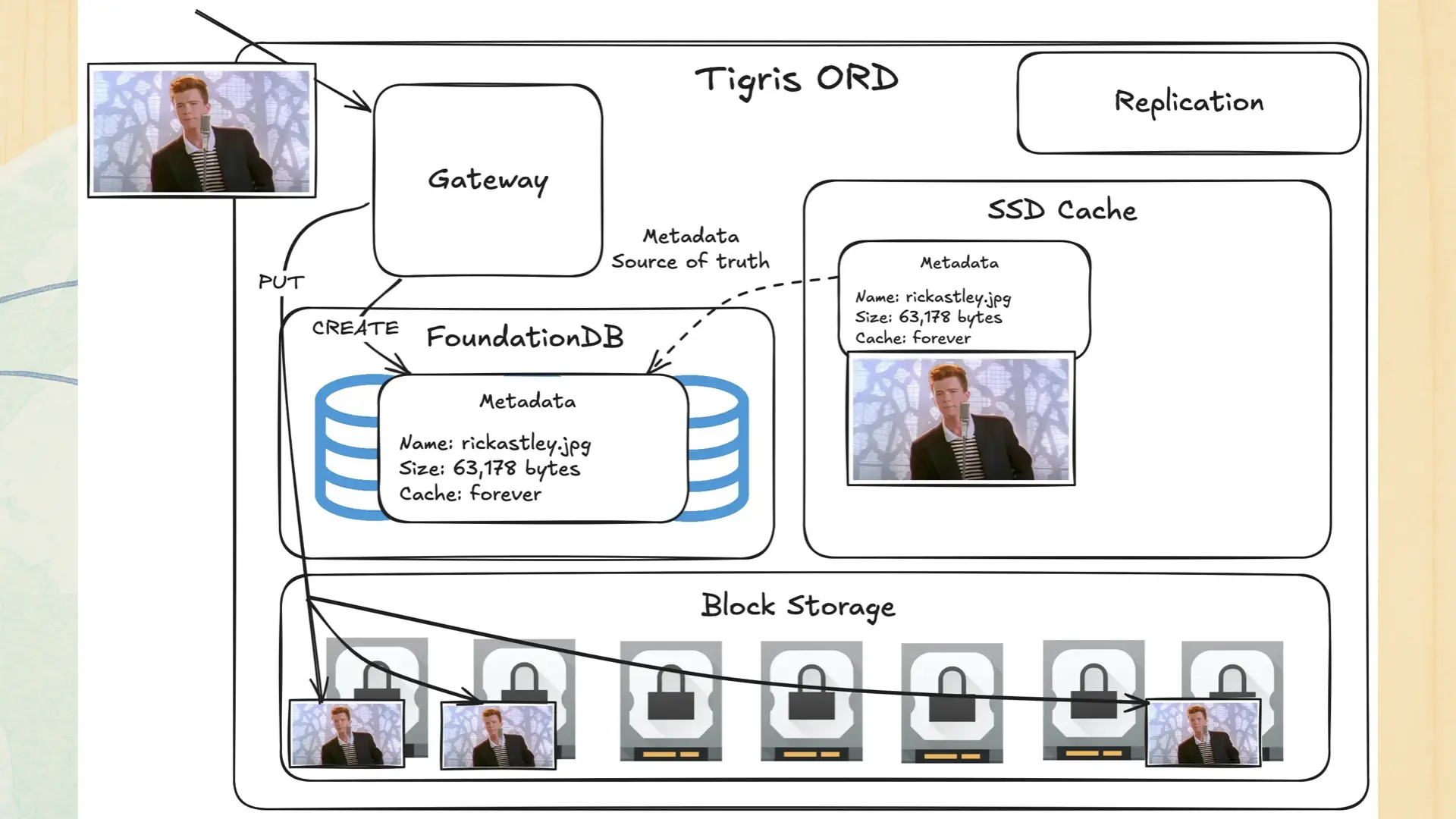

Let’s see how that works in action. You upload that pic o rick to San Jose. Then on the inside something like this happens:

The picture hits the gateway. The gateway puts metadata into FoundationDB (an ordered key-value store, I’ll get more into this later), a copy in the SSD cache, and n copies of the object in block storage. Then the metadata is queued for replication.

Just assume this is a three tier cache: SSD cache, then data inlined to FoundationDB, then block storage.

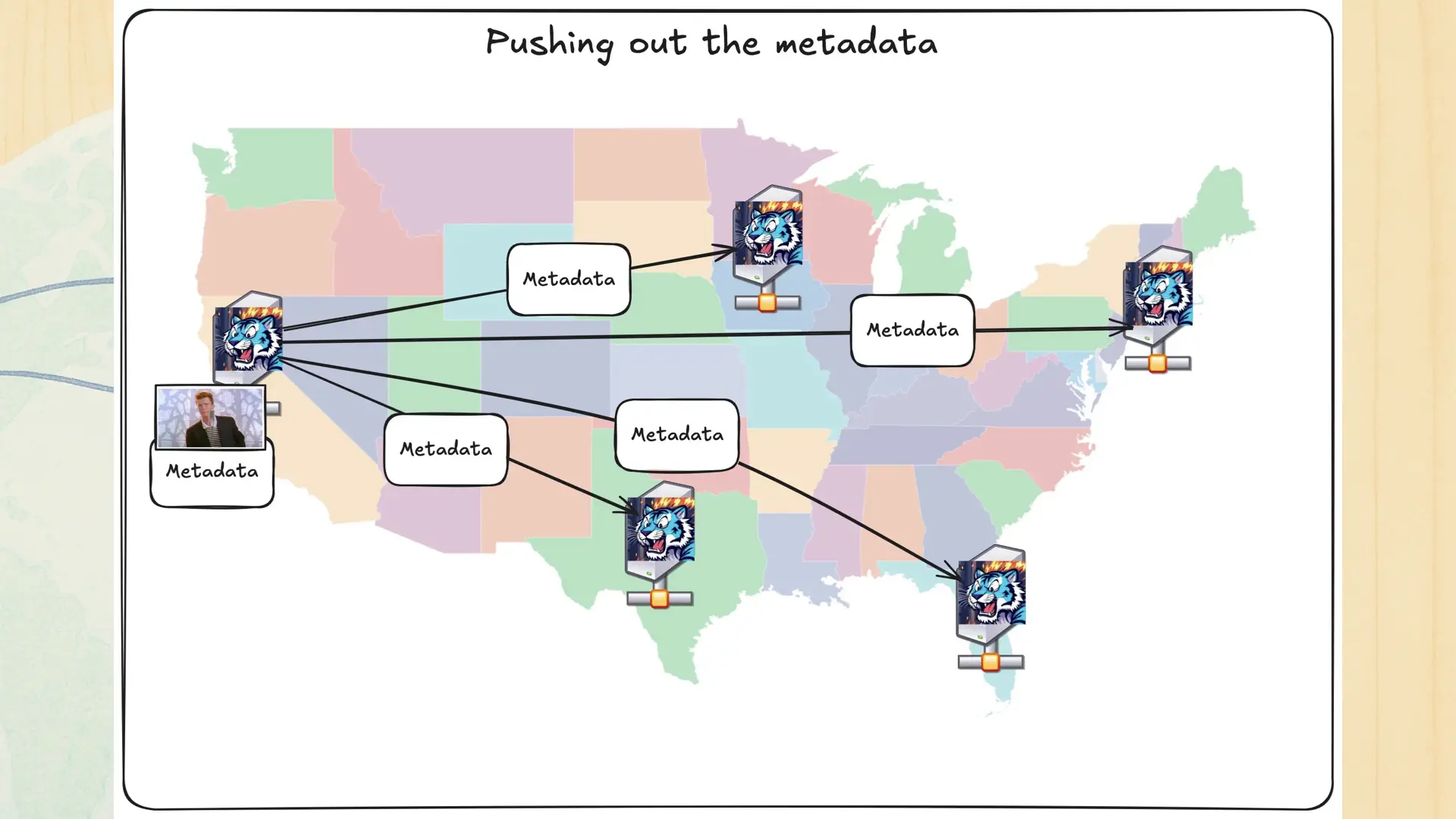

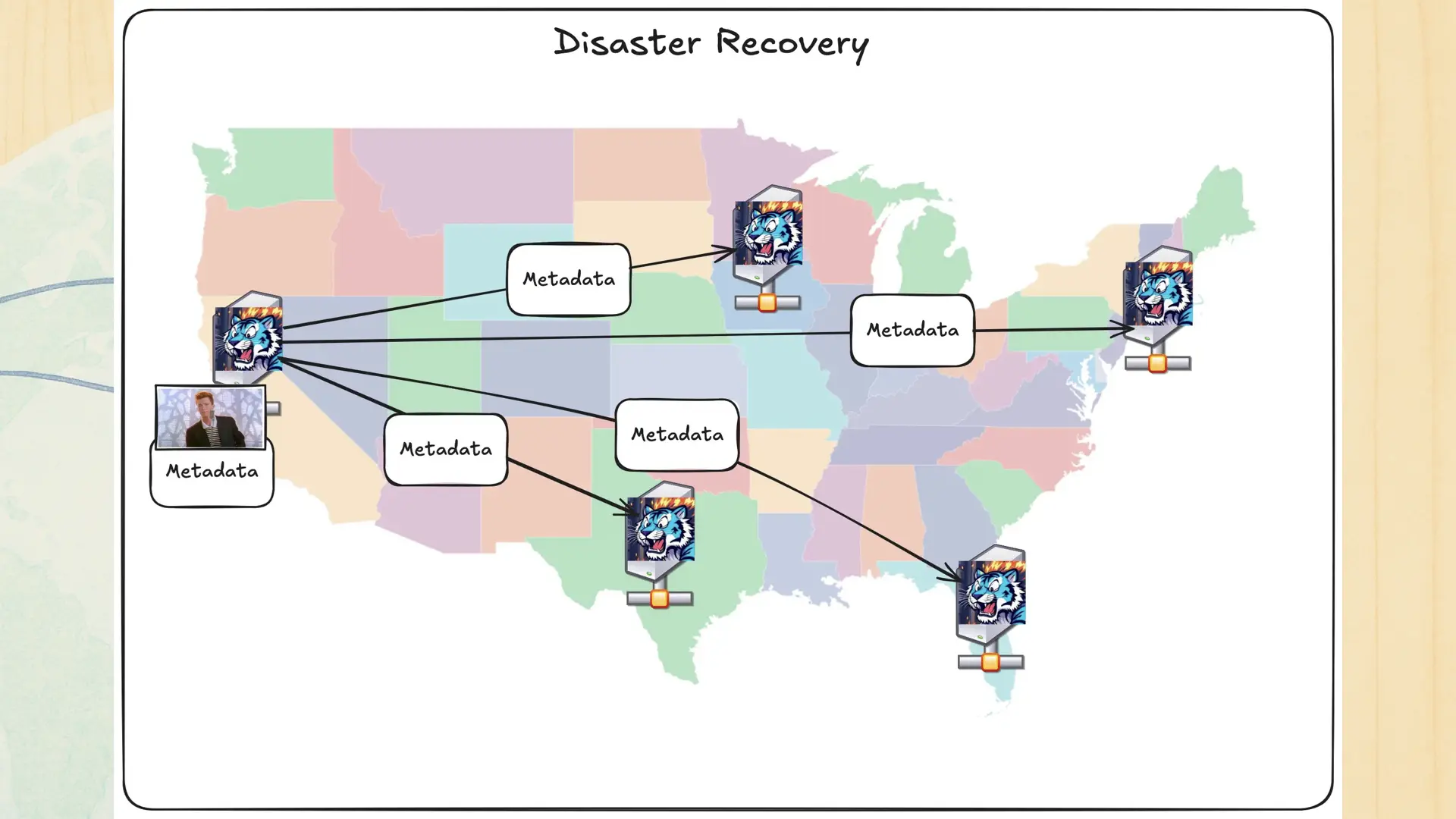

We have a backend service that handles our replication model. When it sees a new record in the replication queue, it eagerly pushes out that metadata to every other region. The coolest part about this in my book is that under the hood, the database is the message queue.

Yes, we really do use FoundationDB as a message queue. There’s one trick to it that’s gonna feel really dumb, and at some level it is. Remember what I said about FoundationDB being an ordered key-value store? There’s something else around us all right now that’s also ordered.

Time. Time is an ordered phenomenon. Every second is after the previous second. No, don’t think about leap seconds, we’re in spherical cow land right now. Either way, a job gets inserted into the future to be handled when it is the present.

If you want to learn more about how this works, it’s based on a paper Apple wrote about how the queue backend works for CloudKit. It’s called QuiCK because it’s a Queue in CloudKit. Our industry is very silly.

Either way, because there’s a queue in the mix to push out the metadata, this can mean that during the tiny bit of time between when an object is uploaded to when the metadata is replicated out, other Tigris regions won’t know that this object exists. This can look like a race condition if your workload is sufficiently global.

We have an escape hatch! You can create buckets with the “Global strong consistency” flag enabled. If you do this, then any interactions with your bucket will be slower because Tigris will mark a single region as the “leader” for that bucket. Any other regions doing requests against your bucket will need to go through that region. You can also enable the strong consistency mode per request if your programming language of choice makes it easy to attach arbitrary headers to your S3 operations.

Usually the default settings are good enough. I’m personally only aware of one customer ever having problems with this.

What about the data?

Looking out there, I see one of you looking a little smug. You probably are thinking to yourself, “sure, this is all about the metadata. Copying metadata around is easy. What about the data?” Let’s go back to the diagrams. We thought about that, but in order to explain how, I’m going to have to peel back the layers a bit more.

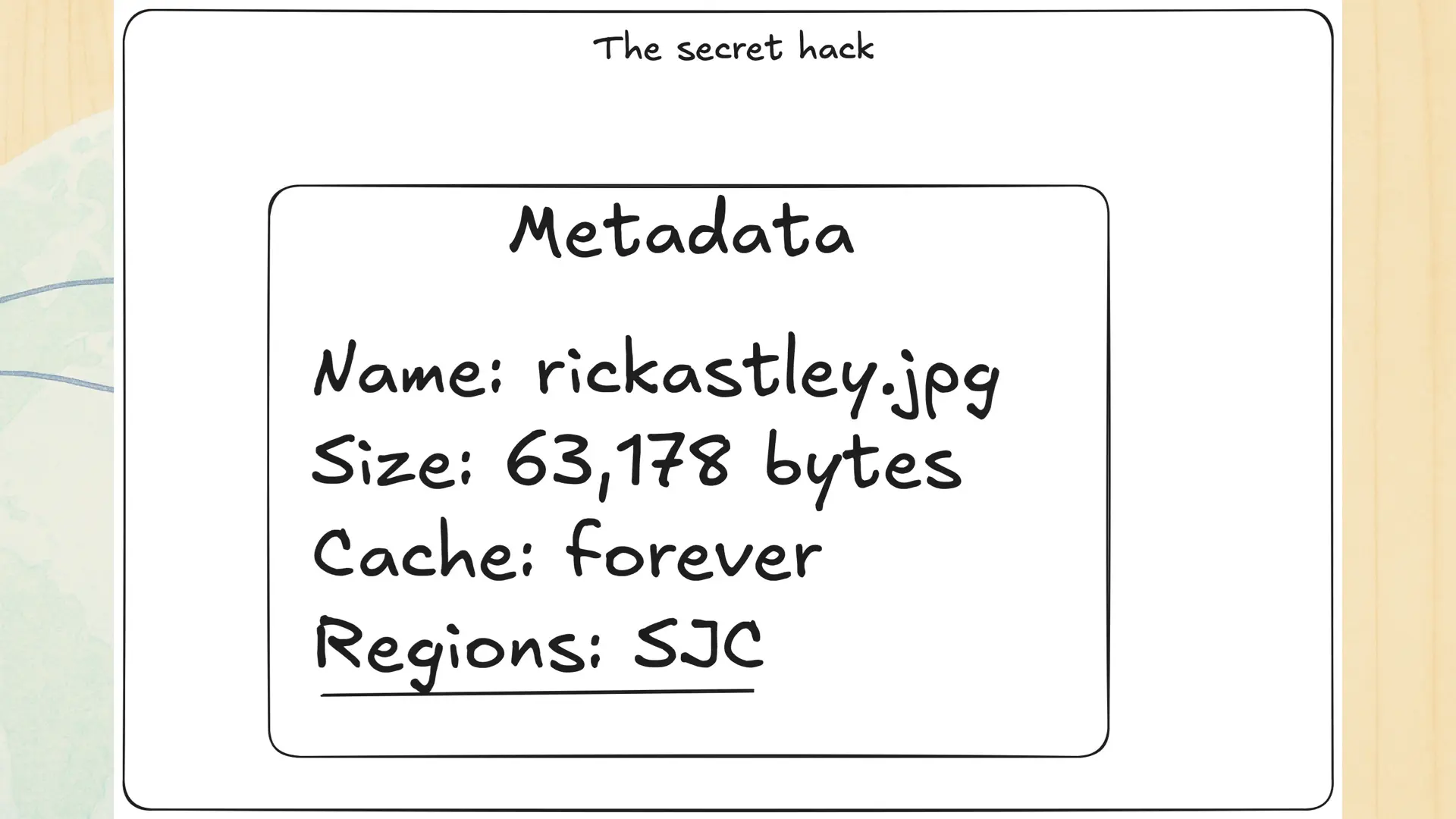

Like I said, you upload the picture and then the replication queue worker pushes it out to the other regions. There’s a dirty trick going on in the metadata. Let’s double-click on it.

Every bit of metadata contains a reference to block storage. Specifically, that reference includes the region that the object lives in. Any region can read from the block storage in any other region. Raise your hand if you see where I’m going here.

So when the Chicago region needs to pull data that only exists in the San Jose region, it makes a copy from San Jose’s block storage layer, then it makes a copy of that data into its local region as it would for any other file. The file gets put into SSD cache, local block storage, and everything else.

Then it updates the metadata to say “yeah, this data’s also in Chicago” and yeets that out to the rest of the hivemind via the replication system.

Do you know what this means? When I said that Tigris is a three tiered caching system, I lied.

This means that there’s actually four tiers to the cache:

- SSD cache

- Data inlined to FoundationDB

- Local block storage

- Remote block storage in another region

This is how Tigris solves that list of hard problems from earlier:

- Your data is stored globally because Tigris pulls it around whenever users need it.

- Your data is always available because as you use it from different regions, it’ll get local copies made globally.

- Your data has the lowest possible latency because Tigris makes sure that your data comes from the closest datacenter possible.

This all adds up to make Tigris even more durable than your big cloud’s object storage service.

The parable of Dalamud

Let’s consider a common SRE parable:

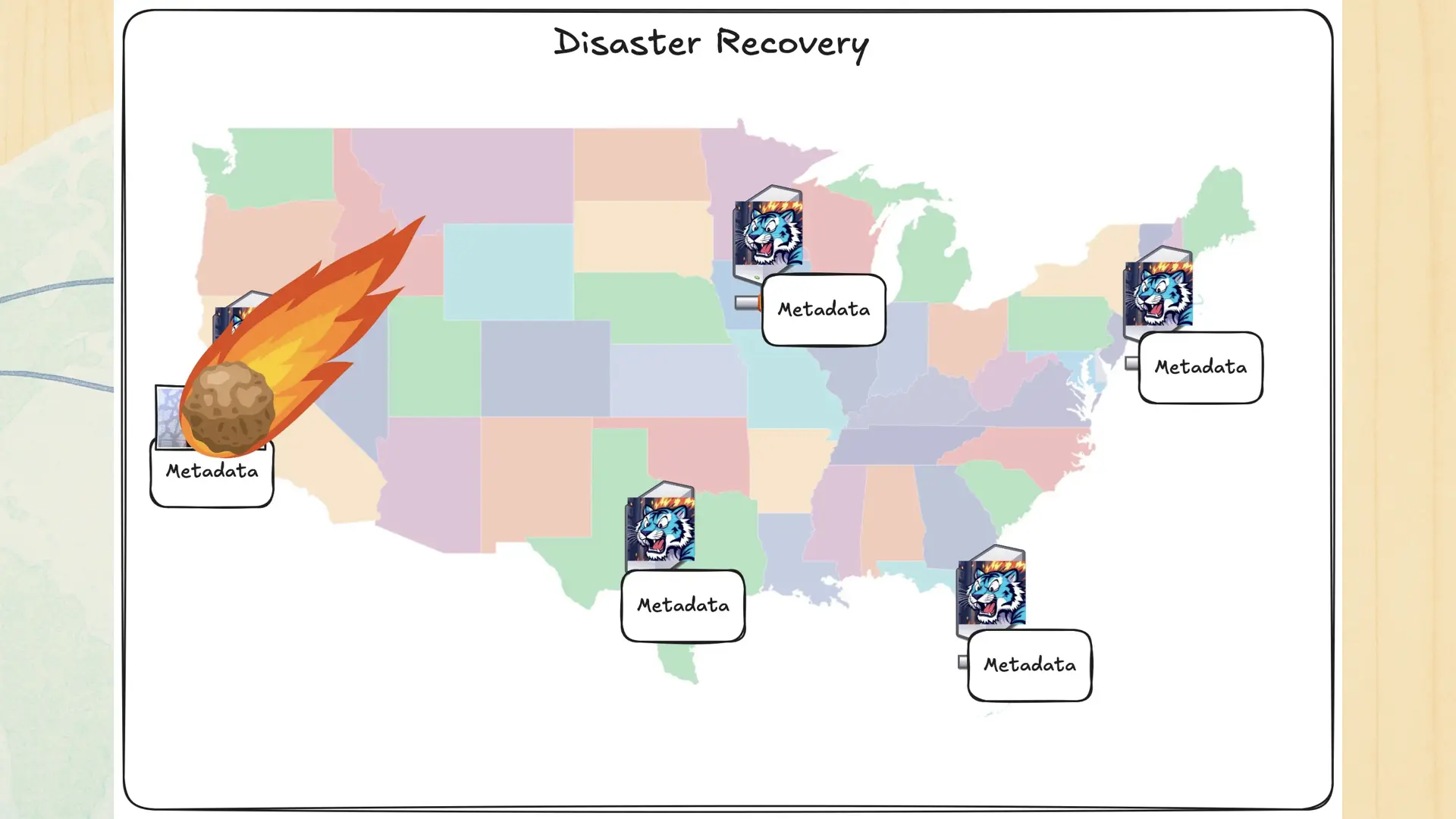

Say you upload that object like usual, but then something that nobody could predict happens:

The San Jose datacenter tragically gets hit by a meteor and is totally knocked offline. You manage to avoid the brunt of the damage due to being in Halifax, but what happened to the data? The BGP constellation reintegrates and you make a request. The picture loads. What? Why?

There’s a few dirty tricks at play:

- Anycast routing or using the public Internet as a load balancer means that Tigris can survive entire regions going offline with the only evidence for users being slightly higher latency.

- The dirtier one is that some parts of block storage is stored separately from the rest of the infrastructure. This means that losing the datacenter doesn’t mean we lose the data.

This level of hilarious redundancy is what sold me on Tigris enough to not only trust them with my homelab’s backups, but also is why I’m working with them and standing up here today.

However, the absolute best part is what you have to do to enable all of this. Here is what you have to do to enable this level of global redundancy:

- Create a bucket.

- Upload data to that bucket.

- There is no step 3.

Wait, hold on, is this the right slide deck? That can’t be it, right? pause I’m kidding, there is no step 3. As your users and workflows read the data from different regions, it’ll just get replicated and cached globally.

Yep! This is on by default. You can’t forget to opt into this. This isn’t a value-added feature that is charged out the wazoo for. It’s just on and it just works. It’s kinda glorious.

What about acronym compliance?

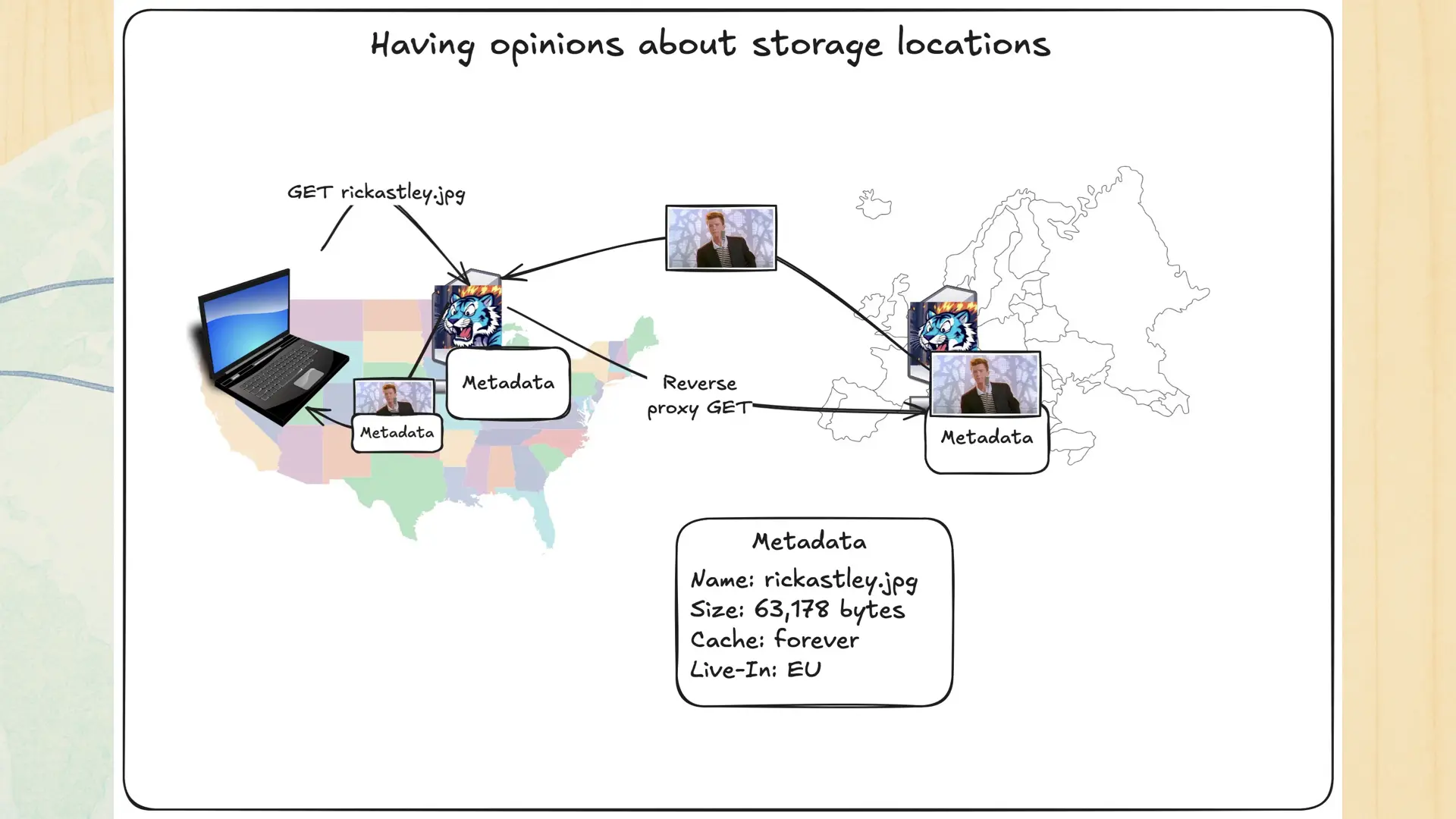

However, sometimes you need to have opinions about how data is distributed. This all adds up to an annoying practice I’ve been calling Acronym Compliance. It’s where there’s a bunch of rules that you have to follow about how and why data is stored and processed. This is onerous and only really exists because our industry failed to self-regulate. How can you handle that in your distributed systems? Here’s what Tigris does:

However, sometimes you need to have opinions about how data is distributed. This all adds up to an annoying practice I’ve been calling Acronym Compliance. It’s where there’s a bunch of rules that you have to follow about how and why data is stored and processed. This is onerous and only really exists because our industry failed to self-regulate. How can you handle that in your distributed systems? Here’s what Tigris does:

When users or automation outside the EU requests objects constrained to live in the EU, Tigris reverse proxies the requests through to the EU. This will make downloading very large objects slower especially if you do a cross-continent operation, but you can rest assured that your EU-bound data will permanently reside in the EU. This also works for individual regions too, so you can cordon your data over to Singapore as easily as you can to Chicago. You can also do this at a per object level. See how by asking me after class!

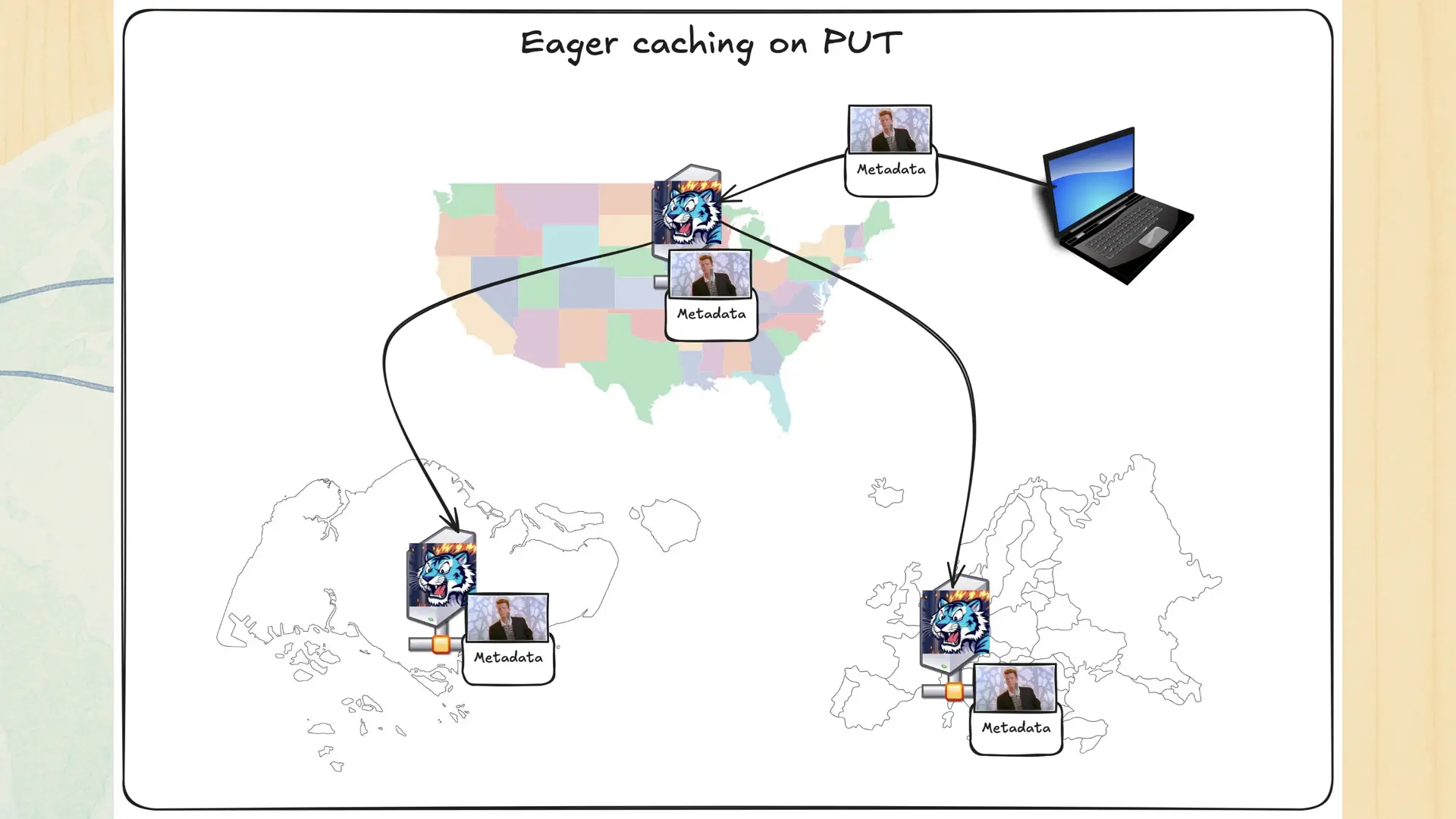

Remember how I talked about push-based replication? Turns out that it’s a very useful thing to have sometimes. You don’t need it often, but in practice you need it just often enough that Tigris baked it into the core. Enable the accelerate flag for the bucket and when you upload the data to one region, it gets pushed out to a few other regions to make things faster.

This gives you a lot of the latency advantages of a push-oriented architecture as well as letting the other regions fall back to the pull-through behaviour. It’s the best of both worlds.

Conclusion

And that’s basically it! We covered a lot of things today. Let’s go over the biggest lessons so that I can hopefully nerd snipe you into making the future resilient.

- Hack the speed of light: Hack the speed of light into your favour by putting your data all over the world.

- Data is high inertia: Data is very high inertia. Once you put it somewhere it’s hard to move it. What if you did hundreds or thousands of micro-migrations per day to make sure that your data is where it needs to be before you need it?

- Use the whole database: You downloaded the whole database, use the whole database in your favour. Take advantage of second or third order properties of things to let you build invincible infrastructure without having to install Kafka. Why shouldn’t you be able to insert data and jobs with the same transaction?

- Every replication strategy is wrong: There’s parts of each major replication strategy that are more or less useful than the others. Tigris combines push-oriented and pull-oriented replication to get things working reliably across the globe.

- Make features you want people to use on by default: If you have advanced features on your platform that you really want people to use, features that literally define your product compared to the others, make them on by default and free to use. If users can’t forget to turn it on, they won’t.

Before we finish this off, I just want to thank everyone on this list for your feedback, moral support, and/or contributions towards my plan of total world domination. If you’re on this list, you know what you did. If you’re not, you know what you need to do.

And with that, I've been Xe! Thanks for having me out here. I'll be around with stickers and if you have questions about Tigris. Have a great day, I hope the coffee is doing more for you than it is for me, and stay temperature out there today. It's gonna be lovely out.